Expedite your nonfiction book discovery process with Readara interviews, summaries and recommendations, Broaden your knowledge and gain insights from leading experts and scholars

In-depth, hour-long interviews with notable nonfiction authors, Gain new perspectives and ideas from the writer’s expertise and research, Valuable resource for readers and researchers

Optimize your book discovery process, Four-to eight-page summaries prepared by subject matter experts, Quickly review the book’s central messages and range of content

Books are handpicked covering a wide range of important categories and topics, Selected authors are subject experts, field professionals, or distinguished academics

Our editorial team includes books offering insights, unique views and researched-narratives in categories, Trade shows and book fairs, Book signings and in person author talks,Webinars and online events

Connect with editors and designers,Discover PR & marketing services providers, Source printers and related service providers

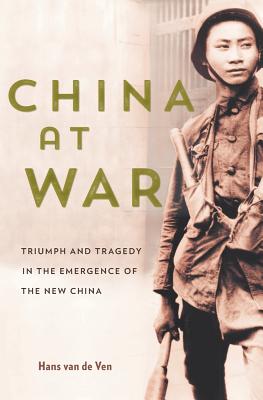

China at War: Triumph and Tragedy in the Emergence of the New China

History > Asia - China

- Harvard University Press

- Hardcover

- 9780674983502

- 9.2 X 6.4 X 1.2 inches

- 1.5 pounds

- History > Asia - China

- (Single Author) Asian American

- English

Readara.com

Book Description

China's mid-twentieth-century wars pose extraordinary interpretive challenges. The issue is not just that the Chinese fought for such a long time--from the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of July 1937 until the close of the Korean War in 1953--across such vast territory. As Hans van de Ven explains, the greatest puzzles lie in understanding China's simultaneous external and internal wars. Much is at stake, politically, in how this story is told.

Today in its official history and public commemorations, the People's Republic asserts Chinese unity against Japan during World War II. But this overwrites the era's stark divisions between Communists and Nationalists, increasingly erasing the civil war from memory. Van de Ven argues that the war with Japan, the civil war, and its aftermath were in fact of a piece--a singular process of conflict and political change. Reintegrating the Communist uprising with the Sino-Japanese War, he shows how the Communists took advantage of wartime to increase their appeal, how fissures between the Nationalists and Communists affected anti-Japanese resistance, and how the fractious coalition fostered conditions for revolution.

In the process, the Chinese invented an influential paradigm of war, wherein the Clausewitzian model of total war between well-defined interstate enemies gave way to murky campaigns of national liberation involving diverse domestic and outside belligerents. This history disappears when the realities of China's mid-century conflicts are stripped from public view. China at War recovers them.

Author Bio

I still don't have a very good answer as to why studying Chinese history has become my life passion. When I decided to learn Chinese in high school, I knew little about China, the Chinese language, or the country’s history. But somehow I have never been tempted to do something else.

Part of the reason is because the path on which this one unconsidered decision put me opened up all kinds of great opportunities: long periods in China and Taiwan, study with some wonderful teachers, and some ten years in the US where I met my wife and made many good friends.

But also, Chinese history has always proved fascinating. I am at my happiest sitting in an archive or library in China, travelling through the country trying to learn more about a place important in my research, or talking about Chinese history with colleagues and friends at a university in China. And there is something very special to see former students build up lives focused on China.

Following my undergraduate studies in Sinology at Leiden University, I went to Harvard University to study modern Chinese history. Seven years later I had a Ph.D. and went to UC Berkeley as a Postdoctoral Fellow. The rest of my career has been spent at Cambridge University.

My first book From Friend to Comrade: the Founding of the Chinese Communist Party (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991) was awarded the Philip Lilienthal Prize of the University of California Press for best first book in Asian Studies.

Like all academics, I have enjoyed my sabbaticals. A British Academy Research Readership made it possible for me to spend three years away from teaching. One of these I spent as a Visiting Scholar at the Academia Sinica in Taiwan.

More recently I have been a Fellow for a year at the Johns Hopkins – Nanjing University Center for US-China Cultural Exchange. I am also a Guest Professor at the Department of History of Nanjing University. I am a Fellow of the British Academy.

Research interests:

- History of the Chinese Communist Party before 1949

- The history of warfare in modern China from the Taiping Rebellion to the Civil War between the Communists and the Nationalists

- The history of Chinese globalization in the 1850-1950 period

Source: University of Cambridge Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies

Videos

No Videos

Community reviews

No Community reviews